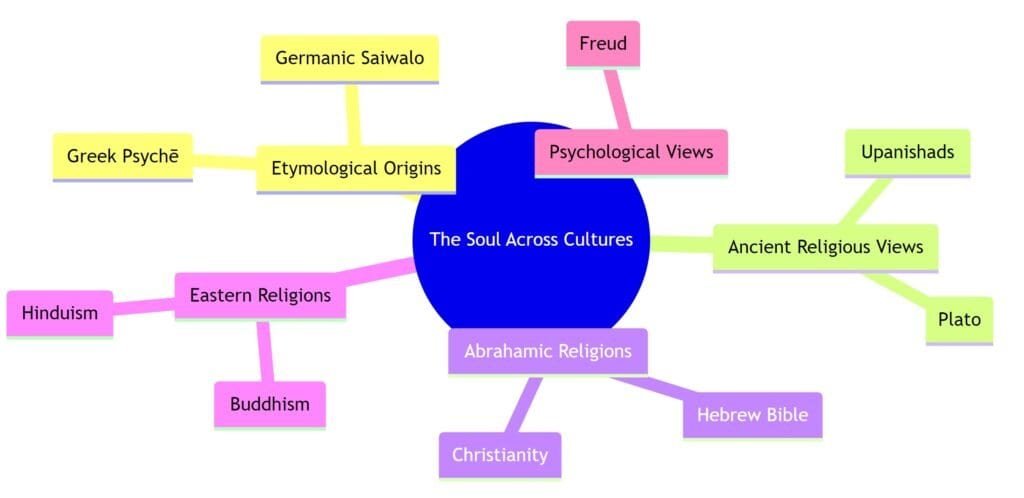

Tracing the History and Meaning of the Soul Across Cultures

The idea of the “soul” has captivated humanity since ancient times. Throughout history, perspectives on the essence of the soul have significantly evolved, from religious and philosophical speculation to psychological and scientific models. This article explores the origins and changing definitions of the soul across cultural and intellectual traditions. It synthesizes viewpoints from ancient religions, Eastern philosophies, Western thought, and contemporary science. While tangible proof of the soul’s existence remains elusive, its symbolic relevance is a metaphor for the multifaceted nature of human interiority. The following provides a wide-ranging survey of soul-concepts through the ages.

Etymological Origins

The English word “soul” derives from the Germanic “saiwalo,” meaning “coming from the sea/lake.” This suggests an early association between the soul and water as the source of life. Sáwol or sáwel comes from the Old High German sêula, sêla. The Germanic word is a translation of the Greek psychē (ψυχή- “life, spirit, consciousness”) by missionaries such as Ulfila, apostle to the Goths (fourth century C.E.).

The Sufi mystic Al-Ghazali epitomized this oceanic connection: “The soul is like a drop of the ocean which contains all the ocean in it.” This poetic metaphor conveys the soul’s divine essence and limitless depth.

The Soul in Indigenous Cultures

Indigenous cultures worldwide offer unique perspectives on the concept of the soul. For instance, Native American beliefs often center around the idea that everything in nature has a spirit or soul. This interconnectedness of all life forms challenges our conventional understanding of individuality and separation. In Australian Aboriginal spirituality, “Dreamtime” represents the soul’s eternal existence, transcending the limitations of time and space.

Ancient Religious Views

In ancient religions and philosophies, the soul was seen as the spiritual essence or animating force within living beings.

One of the earliest records of a concept similar to the soul comes from ancient Egypt. Egyptians believed humans possessed a “ka” – a spiritual double that remained after death. The ka needed to be preserved as much as the physical body.

The Upanishads, the ancient Hindu scriptures, contain one of the earliest references to the concept of the soul in human history. Between 800 and 500 BCE, the Upanishads introduced the idea of the atman – the eternal core of a person identical to the unchanging, universal Brahman. However, schools of thought diverge on whether the atman is truly unified or an illusion. Hindu texts also describe various aspects of the soul as permeating the body, including the hridyatman (heart self), manomayakosha (mind self), and pranamayakosha (breath self).

“The being who is in the sun, I am he. The being who is in the moon, I am he. The being who is in the lightning, I am he. The being who is in the ether, I am he.” Brihadaranyaka Upanishad

Help support this site – we receive a small commission from Amazon links on this page.

In works like the Phaedo, Phaedrus, and The Republic, the ancient Greek philosopher Plato described the soul as the incorporeal and immortal essence of a person, which animates the physical body.

“The soul, then, as being immortal, and having been born again many times, and having seen all things that exist, whether in this world or the world below, has knowledge of them all.” – Plato

Abrahamic Religions

In the Abrahamic faiths of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the soul is seen as the immortal part of a human, which lives on after the body’s death.

The Hebrew Bible refers to the soul as the nefesh or neshama. The Talmud states, “The soul of man is a lamp of God.” In Christianity, the soul is believed to be created by God and imbued with higher faculties like morality and reason.

“What shall it profit a man if he gain the whole world and suffer the loss of his soul.” – Jesus (Mark 8:36)

The journey of the soul is a prominent theme for many spiritual teachers and saints across religious traditions. In 16th century Spain, St. John of the Cross penned his famous poem “The Dark Night of the Soul,” which describes the soul’s quest for union with the Divine. St. John portrays the “dark night of the soul” as a painful but necessary phase along the pathway to mystical enlightenment. The soul must experience purification and isolation from earthly attachments before ascending to God. There is light beyond the darkness if one persists lovingly.

St. John writes: “Oh night more lovely than the dawn, Oh night that joined Beloved with lover, Lover transformed in the Beloved.”

His poetic imagery casts the soul’s struggles positively, as opportunities for greater closeness to the Source. For St. John and other mystics, nurturing the soul is essential to finding inner peace and fulfilling one’s spiritual destiny.

The Soul in Mystical Traditions

Mystical traditions within Abrahamic religions offer unique perspectives on the soul. In Judaism, Kabbalah teaches that the soul has multiple layers, each serving a different purpose in connecting us to the Divine. Sufism focuses on the soul’s journey towards divine love and enlightenment. Sufi practices like “dhikr” (remembrance of God) aim to purify the soul and bring it closer to the Divine.

The Sufi mystic and poet Jalal ad-Din Rumi wrote about the soul’s journey towards the divine:

“I died as mineral and became a plant. I died as plant and rose to animal. I died as animal and I was human. Why should I fear? When was I less by dying?”

Eastern Religions

In Hinduism, the atman is the eternal self or “soul.” Reincarnation of this essence into new bodies is a core belief. The Bhagavad Gita states:

“Just as a man casts off his worn out clothes and puts on new ones, so the embodied self casts off its worn out bodies and enters into new ones.”

Buddhism starkly contrasts, arguing there is no unchanging, eternal soul (anatta). The Buddha taught:

“This person consists of the four great elements…when this person dies, earth returns to and merges with the earth-body…water returns to and merges with the water-body…fire returns to and merges with the fire-body…air returns to and merges with the air-body…faculties entirely scatter and merge with the corresponding realms.”

The Field of the Soul

The soul is not an isolated entity but exists within a field. This field is a boundless and nonlocal presence that transcends all spatial extensions. Imagine a vast ocean where each drop is a soul (a holographic point of the whole), yet the ocean itself is also the soul. This interconnectedness challenges our conventional understanding of individuality and separation.

The soul is the field of consciousness in which all experience happens. The individual consciousness is our unique soul, though there are no separate souls, as the experiential field is a continuous whole. From nondual awareness, distinctness and uniqueness do not require separateness.

Psychological Views

While early thinkers focused on the soul as an immortal object, later philosophers began examining it empirically.

In the late 19th century, Sigmund Freud put forth a new model of the human psyche. He explicitly used the German word “die seele” meaning “soul” or “psyche” rather than “mind.” Freud sought to explain the psyche scientifically, intentionally avoiding traditional notions of the eternal soul. His model of id, ego, and superego delved into the unconscious forces shaping personality and subjectivity.

The Soul in New Age Spirituality

New Age spirituality, influenced by Eastern and Western philosophies, offers a smorgasbord of views on the soul. Concepts like “soulmates,” “old souls,” and “soul contracts” have entered the popular lexicon, suggesting predestined relationships and life paths. The idea of “soul retrieval” in shamanic practices aims to recover lost pieces of the soul due to trauma or disconnection.

The Soul in Popular Culture

The concept of the soul finds frequent expression in literature, music, and film. From Disney’s “Soul” to literary classics like “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” the soul is often portrayed as the seat of morality, identity, and the human experience. These portrayals sometimes offer modern reinterpretations that challenge traditional views.

Synthesis of Perspectives

The contemporary view sees the soul as representing the depth of human experience. While the tangible existence of the soul is no longer a given in a scientific worldview, its meaning persists as a metaphor to describe the totality of our inner worlds.

Above or Below, where does the soul go?

Many modern religions espouse the idea that the eternal souls of the virtuous ascend to Heaven in the sky while the souls of the wicked descend into the underground Hell. However, beliefs about the afterlife’s geography have not always followed this pattern across cultures and history.

In the religions of ancient civilizations like Greece and Egypt, the default destination of souls was not the heights of Heaven but the depths of the underworld. Ancient Greek mythology located the domain of Hades deep underground. Here, most souls wandered amongst shadows, while heroes like Hercules could hope for the celestial heights of Mount Olympus. Similarly, ancient Egyptian souls faced a perilous journey to the subterranean kingdom ruled by Osiris. Only pharaohs could join the eternal stars.

So while up is Heaven and down is Hell forms a typical pattern today, the contrasting visions of the Greeks and Egyptians demonstrate this was not a universal conception. Their underworld realms for the dead reveal different cultural maps of the afterlife’s orientation. Only later, with Zoroastrianism’s division and the Abrahamic faiths’ focus on Heaven above, did the association of virtue with height and vice with depth take hold.

While modern imaginations may look upward to divine rewards and downward to demonic punishments, the ancient dead were more often thought to sink below the earth itself. The afterlife’s geography depends greatly on one’s religious worldview.